The Making of Fleetwood Mac's 'Tango In The Night'

How battles with addiction, strained relationships, and new recording technology led to an unforgettable album.

Fleetwood Mac’s most famous records were often born out of the group’s collective musical genius and a lifestyle seeped in drugs, alcohol, in-fighting, and heartbreak. Testimony from people like late Record Plant co-founder Chris Stone, who witnessed the making of Rumours, puts the chaos behind their brilliance into striking perspective. “The band would come in at 7 at night, have a big feast, party ‘til 1 or 2 in the morning,” he told Paul Verna in a 1997 Billboard interview. “And then when they were so whacked-out they couldn’t do anything, they’d start recording. They finally had to straighten out, but they spent so much money it was probably the biggest album we had done to date.”

Unfortunately, the drunken all-night parties and excessive cocaine consumption took a serious toll in the eight years after the release of Rumours. Stevie Nicks—whose beautifully sung vocals played a key part in many of Fleetwood Mac’s biggest hits—underwent treatment at the Betty Ford clinic for cocaine addiction in 1985. Though she overcame her drug habit before the band started working on Tango In The Night later that year, an alcohol dependency and misuse of the anxiety medication Klonopin severely impeded her participation in the recording process.

Nicks wasn’t the only band member in rough shape. Mick Fleetwood’s coke consumption and reckless spending had gotten so bad that he had to sell his mansion, his collection of fancy cars, and the plaques from Fleetwood Mac’s best-selling albums in 1985. After losing everything, he was relegated a makeshift bedroom in Tango in the Night co-producer Richard Dashut’s house until he got back on his feet.

Self-destruction and a general sense of unease seemed to permeate every group member’s life. “Everyone was at their worst, including myself,” Lindsey Buckingham told Nigel Williamson in a 2013 Uncut interview. “We’d made the progression from what could be seen as an acceptable or excusable amount of drug use to a situation where we had all hit the wall. I think of it as our darkest period.”

Despite the darkness, damaged interpersonal relationships, and respective battles with substance abuse, Tango in the Night started to take shape in late 1985. Buckingham, who was in the process of working on his third solo record at the time, halted production to focus on recording the group’s first album in five years. “I guess you could say the needs of the many outweighed the needs of the few,” he told David Wild in a 1987 Rolling Stone interview.

Realizing that after 20 years of existence Fleetwood Mac was moving apart from one another in ways that might lead to their ultimate dissolution, Buckingham swung for the fences while recording their potential swan song. “I decided, if we’re going to do this, then let’s really do this,” he told Rolling Stone. “This could very well be the last Fleetwood Mac album, so let’s make it a killer.”

To capture the right sound, the band elicited help from aforementioned co-producer Richard Dashut and engineer Greg Droman. Dashut’s name likely rings a few bells for avid Fleetwood Mac fans, as he co-produced seminal records like Rumours, Tusk, and Mirage. Despite the familiarity of faithful co-producer Dashut, Tango In The Night also marked a new chapter in the band’s existence. It was the first Dashut/Fleetwood Mac collaboration that didn’t include fellow co-producer Ken Caillat.

Dashut’s production chops may have been well established when recording sessions began, but Greg Droman was far more green as a studio engineer. "I didn't know what the hell I was really doing," he admitted in a 2017 Salon interview with Annie Zaleski. "I really didn't.”

Despite his self-deprecating description of his abilities, Droman quickly realized that the band didn’t care much about technical mastery or lack of it. They just wanted supportive people in the studio who understood their collective vision. “I learned pretty quickly that just the personal vibe of them feeling comfortable made as much difference as what you knew,” Droman told Salon.

This interesting mix of seasoned veteran co-producer and novice engineer, combined with elite studio mastery and sonic visions of Lindsey Buckingham, seemed to be just what the band needed to introduce a new sound that combined elements of polished 80s pop hits and rock 'n' roll. “On a production level, it’s beyond anything we’ve done,” Buckingham told Rolling Stone.

To help them create new songs that evoked aspects of their earlier classics while simultaneously going in a bold new direction, they opted to record in comfort instead of seeking out a cutting edge studio. “The bulk of it was cut in the home studio that used to be my garage in the Hollywood hills,” Buckingham told Stephen Holden in a 1987 New York Times interview.

Home studio sessions may have been Buckingham’s preferred method, but the rest of the band wasn’t quite as comfortable on his turf. Not wanting to overstep the delicate lines of personal space, the other Fleetwood Mac members rented a massive RV, parked it in his driveway, and spent much of their time in between sessions inside of the giant vehicle. “It was kind of strange,” Dashut told Salon. “It's not like everyone was hanging out together.”

Even with the RV buffer, Buckingham’s ex-partner Nicks understandably found it the most difficult to be in such close proximity of his house. Her fragile mental state and struggle to find sobriety limited her to about two weeks of total time during the year-and-a-half recording odyssey of Tango in the Night. “He lived there with his girlfriend Cheri and this record was being recorded at his house and I didn’t find that to be a great situation for me,” she told Howard Cohen in a 2017 Miami Herald interview. “Especially coming out of rehab.”

The obvious rift between Buckingham and Nicks—combined with her frequent absence from the album’s creation—led to her voice being noticeably absent on significant chunks of the record. To make it all work, Buckingham would stitch pieces of her vocals together or cut then out entirely—a decision Nicks understood in hindsight. “I’d leave and he’d take all my vocals off,” she told the Miami Herald. “And I’m not blaming him for that because I’m sure they totally sucked. Vocals done when you’re crazy and drinking a cup of brandy probably aren’t usually going to be great.”

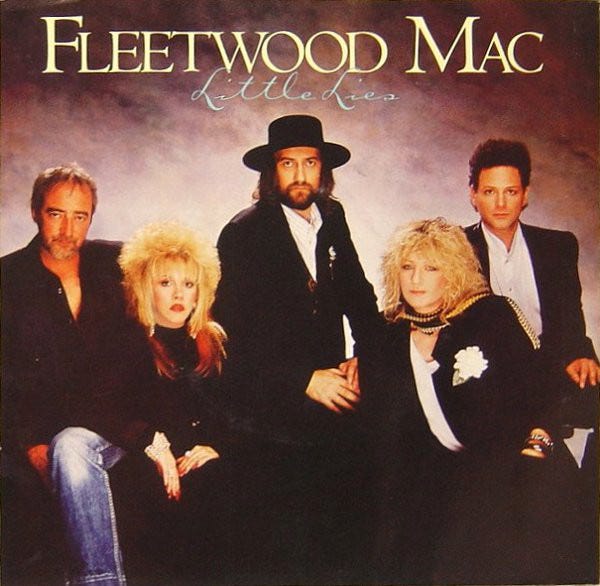

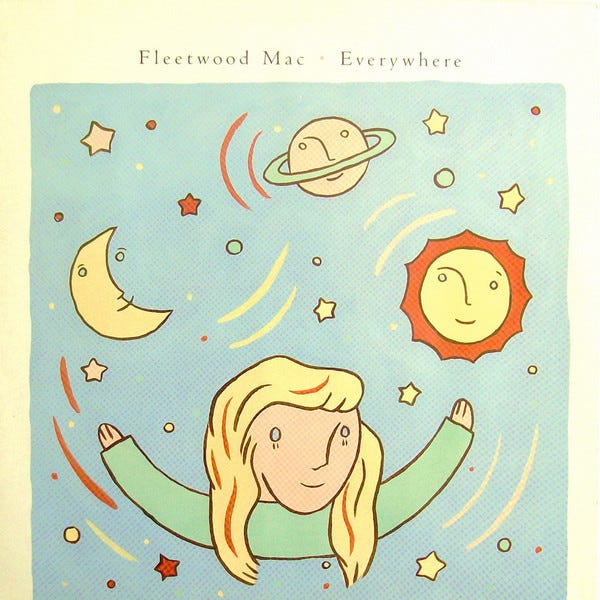

In the end Christine McVie took lead vocal duties on four tracks including the smash hits “Little Lies” and “Everywhere,” Nicks sang lead on two, and Buckingham served as head vocalist on five. Buckingham and Nicks shared the lead on “When I See You Again.”

Despite the fact that personal tensions within the band were significant, Buckingham maintained his trademark obsessive attention to detail on every song—leading to some incredibly rich and layered instrumentation and vocal stacking. “Most of the vocal parts were recorded track by track,” he told the New York Times. “The voices used in the textured vocal choirs were mostly mine.”

Buckingham also took advantage of new musical technology, making great use of the famously expensive Fairlight CMI sampler. Even though his description of toiling away on the Fairlight in isolation is over 30 years old now, it bears a striking similarity to how modern producers might describe their beatmaking process. “I used a Fairlight machine that samples real sounds and blends them orchestrally,” he told the New York Times. “Constructing such elaborate layering is a lot like painting a canvas and is best done in solitude.”

Buckingham’s description of the Fairlight sounds like it was a labor of love, but others involved in the making of Tango in the Night had mixed feeling towards the prevalence of the sampler on the album. “I think the Fairlight started replacing some of that human touch, some of the other band members,” Dashut told Salon. “Lindsey was able to do a lot more on his own and control it a lot more artistically.”

Dashut admitted that he found the cutting edge technology fascinating, but he also missed the sessions from previous albums that involved the entire band working in tandem. “[It was] both an innovative and a very exciting thing that was coming,” he told Salon. “But I also lamented the fact that the band didn't participate as much, as a whole.”

Despite Dashut’s concern about technology replacing group connectivity, there was considerable experimentation with live playing techniques. Sometimes Fleetwood Mac would play at half time and speed up the recording afterwards to play with the textures. They also slowed down their recordings and doubled, tripled, and quadrupled certain sections of the music. Both of these techniques are expanded upon considerably in the Salon article.

Mixing sessions could be exhausting, with each track often taking a full week of tinkering or more before it satisfied all parties. Sometimes Buckingham decided that a song was missing an element and would scrap it entirely before starting over.

The men behind the boards also moved away from analog and used a two-track Sony digital tape machine extensively in getting audio ready for the mastering process. Surprisingly, they found the digital tape kept the spirit and sound of the original recordings in tact better than analog. “The Sony digital machine seemed to preserve what we liked about the sound of the original tracks better,” Droman told Salon. “The analog machine ‘smeared’ the sounds.”

Use of the new digital tape technology didn’t come without a price. The tape reels—which had been manually spliced together—started making odd noises during the mastering process. In an era well before backups were both easily achieved and commonplace, the possibility of losing 18 months worth of hard work because of tape imperfections was a terrifying prospect.

Thankfully that flaws were repaired and the record ended up sounding great, but Droman can still hear disparate fragments with his engineer’s ear. “There's something on one song—I think it's 'Little Lies,’” he told Salon. “You could easily say ‘Oh that's a hi-hat.’ But it's not. I know it's not.”

Though the band was seemingly able to co-exist—albeit tersely—for the majority of the 18-month recording process, wrapping up Tango in the Night proved to be rather bittersweet exercise. Buckingham, who was exhausted, burned out, and frustrated with his team of collaborators, decided that embarking on an extended tour with everyone would push him to a breaking point. “When I was done with the record, I said, ‘Oh my God. That was the worst recording experience of my life,’” he told Uncut. “And compared to making an album, in my experience, going on the road will multiply the craziness by times five. I just wasn’t up for that.”

Guitarists Rick Vito and Billy Burnette subsequently replaced Buckingham for the tour and remained in the group for several years.

Buckingham’s departure may have soured the completion of Tango in the Night, but it was still a return to form for Fleetwood Mac’s classic lineup of Lindsey Buckingham, Mick Fleetwood, Christine McVie, John McVie, and Stevie Nicks—providing them with their biggest critical and commercial success since Rumours set the world on fire in 1977. The singles “Big Love,” “Little Lies,” “Everywhere,” and “Seven Wonders,” all cracked the Billboard Top 20 and the album sold in excess of three million copies as of 2000.

Though the classic lineup hasn’t made another album together in the 32 years since, it seems Fleetwood Mac’s last collective effort was symbolic of them growing up and moving on to a new chapter in their respective lives.

While fans may crave one final project while everyone still has their health, perhaps Tango in the Night serves as a perfect farewell—one that shouldn’t be tampered with.

Thanks for reading, see you on Wednesday!

Mr. Sorcinelli, I loved this article and thank you for writing it. But I was wondering if you could provide any info about an issue it doesn't address (perhaps because it amounts to nothing more than, no pun intended, rumors!).

For years I've heard here and there on the internet that Mick Fleetwood and maybe John McVie were in such bad shape at the time of the making of Tango in the Night that one or both of them contributed either little or absolutely nothing to the actual making of the music on the record. That one or both of them was even barred from the studio (by Buckingham?) and just showed up for the album's photo shoot.

Do you know if there's any truth to that? Did either or both of them not play anything, or play little, for the album? Or were they all-in contributors to the recording sessions? Or somewhere in between?

Thanx -- Matthew