The Leon Sylvers III Interview Part 2

Reflections on reverse engineering Motown, the series of coincidences and the 100-person recording session that led to The Sylvers' "Don't Stop, Get Up," and Leon's early years with SOLAR.

Click here to read for Part 1 of my conversation with Leon Sylvers III.

With The Sylvers debut LP wrapped and “Misdemeanor” making its rounds as a hit record, Leon knew that nothing in the industry was promised—so he continued to put in long, hard hours practicing the bass. This insured he was always ready to execute any task required of him in the studio. “If we had to go over it more than one or two times, I wanted my fingers in shape,” he says. “Everything I did, I knew it was going to be hard. So I assumed it and just took it on like that.”

He now considers his diligence a critical part of his artistic growth that helped him compensate for a lack of formal training. “I think that was part of the maturation, as far as embedding that technique into my creative process,” he says. “How I practiced, it was based off everything new, ‘cause I wasn't taught no kind of way.”

In addition to neverending practice sessions, Leon also tried to reverse engineer his favorite Motown records during his free time to understand the complex dynamics of sound at play. Hours spent intently studying the famed label’s output helped him better understand the elements needed to arrange, produce, and write a great record. “I called it reverse music in my head,” he says. “I would buy it and then study it and take it apart—the drums the baseline, the melody, the lyrics, how they would able to sing off the beat. And that was part of the process too.”

While Leon continued to immerse himself in solo practice, studio sessions, and Motown record reverse engineering, he quickly realized he had found his life’s calling. “I was so into it,” he says. “I was supposed to do this for the rest of my life, I assume now, because that's what I'm still doing. And I love it.”

As The Sylvers’ second album started to come together, he further honed his songwriting skills by penning the majority of the tracks on the 1973 LP The Sylvers II—a rich, moving album beautifully co-produced by Keg Johnson and Jerry Peters. Much like his bass proficiency and understanding of song arrangement, the language needed to write many songs efficiently came from intense focus and deliberate practice. “When I was in the Nickerson Gardens projects, I would read almost halfway through the dictionary to learn words that nobody used,” he says. “Plus I did poetry before I started writing.”

Though The Sylvers II is now regarded as one of the group’s strongest efforts and was positively received at the time of release, their creative process started to evolve and change as work began on their next album—with Leon writing only two out of 10 tracks on the following year’s The Sylvers III. Pride also folded the same year, making The Sylvers III their final release with MGM.

The Capitol Records releases Showcase (featuring the hit “Boogie Fever”) and Something Special (featuring the hits “Hot Line” and “High School Dance”) both saw Leon write or co-write four out of 10 tracks. The group then self-produced their final album on Capitol, 1977’s New Horizons, marking the next major turning point in his career.

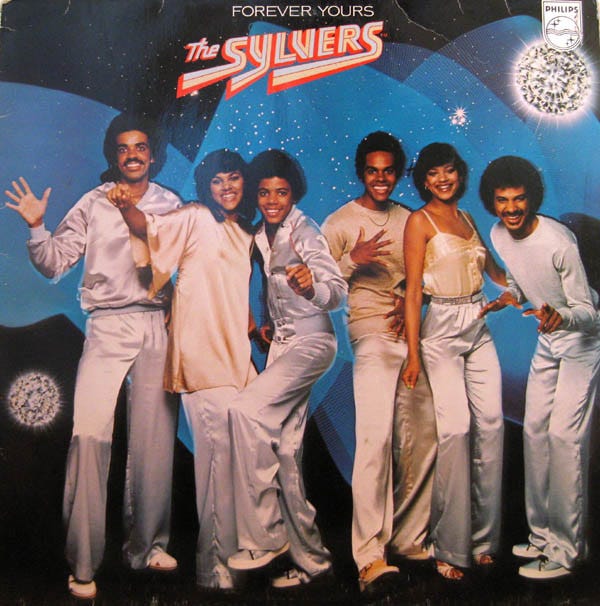

Leon’s move towards production began with The Sylvers 1978 release Forever Yours, an album he co-produced alongside Bob Cullen and Al Ross. Like so much of his catalog, the backstories surrounding the relea are plentiful. The LP’s hit record "Don't Stop, Get Off,” for example, was birthed out of a series of coincidences that provided the inspiration for the song’s infectious hook.

First, the group attended a Brother’s Johnson concert together after an extended tour in Japan. When the energy in the show picked up, Leon noticed people in the crowd enthusiastically shouting, “ooh, ooh” to the beat. Immediately intrigued by how good it sounded, he asked the people near him about the chant. “Everybody around me said, ‘Where you been? That's what everybody do when they like something,’” he says. “I was like, ‘Ohhh.’ So I started writing the song right then.”

The rest of the “Don’t Stop, Get Off” chorus came from a Sylvers concert where the group sent Foster out with his bass to warm up the crowd and give the rest of the family a bit more time to get ready. One of the grooves he started to strum had an immediate impact on the crowd. “He had a funky bassline,” Leon says. “And the kids start saying, ‘don’t stop, get off’ to the beat.”

Not one to miss an opportunity for a unique recording, Leon grabbed a boombox that was handy and captured the impromptu bass/chant combo. “I recorded it right there,” he says. “And it was perfect. After the show I was waiting to get back and hear that.”

Though Forever Yours eventually came out on Casablanca, The Sylvers were still with Capitol Records during the recording process. As they set out to make the album version of “Don’t Stop, Get Off” in the studio, Leon asked Bob Cullen to get as many Capitol employees as possible to participate in the “ooh, ooh” part of the song. People showed up in droves and the recording session soon turned into a party. “Almost a hundred from the Capitol building, they came and did that to the beat and stayed,” he says. “It was fun. And it sounded great on record.”

Feeling that the group had captured a soon-to-be trend with the “ooh, ooh” and “don’t stop, get off” chants, Leon pleaded with Larkin Arnold—the head of Capitol’s Black Music Division—to push the single immediately before another act beat them to the punch. He remembers telling the executives at Capitol, “‘This is a new thing. If we get at the beginning of it, this will work because the people created it. And once they hear themselves on radio, it’s a trend.’”

Unfortunately, his please fell on deaf ears. “They didn't understand what it was at Capitol,” hes says. “And so it was one of them things, man—that record sat for almost two years.”

Leon’s frustration grew when songs started coming out to commercial success that featured a similar “ooh, ooh” in the mix. When Foxy released their 1978 single “Get Off” and it proved to be a major hit, it felt like it was too late for The Sylvers’ inventive song to gain any traction. But the group prevailed, eventually finding success with “Don’t Stop, Get Off” during their transition to Casablanca.

Despite the disappointing conclusion to his time at Capitol, the experience of having his input ignored provided a valuable lesson. “That showed me, as a producer, when you get a move like that, when you can catch something like that, it's important to always listen,” he says. “The powers that be didn't understand it, but I did.”

Events were already taking place that would help with Leon’s solo production journey before Forever Yours saw commercial release. The Sylvers had established themselves as a presence on Soul Train early on and quickly won the affections of host Don Cornelius and talent coordinator Dick Griffey (pictured above with Leon). When the two industry icons asked The Sylvers to be part of a Soul Train tour a few years before Griffey founded SOLAR, the siblings eagerly agreed.

During the tour the group worked the the Chi-Lites “Are You My Woman (Tell Me So)” (later sampled by on Beyoncé’s “Crazy in Love” in 2003) into their set with a choreographed step, much to the delight of Griffey. “Dick loved it, he would come on the side of the stage just to see us do that move,” Leon says. “He told me, ‘That that's a bad move Leon. That that's a bad move right there.’”

Leon’s friend Richard Aaron, who had co-produced Jerry Peters’ Blueprint For Discovery with Peters and Keg Johnson, helped cement the business relationship between Griffey and Leon by setting up a meeting between the two men. Never one to show up unprepared, Leon invested $10,000 to cut three master recordings to bring along with some unreleased Sylvers material he had produced.

One of the self-funded recordings later became the Dynasty hit “I Don't Want To Be A Freak (But I Can't Help Myself)” from their 1979 SOLAR debut Your Piece Of The Rock, which Leon produced front to back. The second song he recorded for the meeting was “Take Another Look at Love” from the group’s sophomore album Adventures In The Land Of Music, also entirely produced by Leon. Though the third song never became an official release, the $10,000 investmore proved more than worth it. “It couldn't happen any better,” he says. “Usually when you do that, you kind of write it off as learning, but those two songs royalty wise paid for itself and above paid for itself.”

Before any of the Dynasty material came out, however, Griffey wanted Leon to attend to Shalamar after being impressed by his material during their Richard Aaron-facilitated meeting. His first production credit and hit with the group was 1978’s “Take That to the Bank,” a rhythmically similar number to Dynasty’s “I Don't Want To Be A Freak (But I Can't Help Myself).”

Using the basic rhythm of the song he had cut as a demonstration track for Griffey, Leon focused specifically on the drums first and used a seasoned studio musician who later joined Dynasty to help enhance the song. “I had a cow bell, conga, timbale rig,” he says. “I would bring it studio. And I used Kevin Spencer, who used to play with The Sylvers at that time. He played bass and keyboards. I did the baseline and was singing the melodies and then so he jumped right in.”

Originally inspired by Robert Blake’s catch phrase on the detective TV show Baretta, “Take That to the Bank” established Leon as a producer by providing him with his first hit at SOLAR. The single also set to stage for a remarkable five-year run of successes as the label’s in-house sculptor of sound, with Billboard magazine dubbing him, “the man of the hour in R & B” in a 1981 article.

Click here to read Part 3 of my conversation with Leon Sylvers III.

If you enjoyed this article, please subscribe to the Micro-Chop newsletter to support independent music journalism.