Moving Units Without a Major Label

How small market artists went gold and platinum in the 80s and 90s by believing in themselves and the independent route.

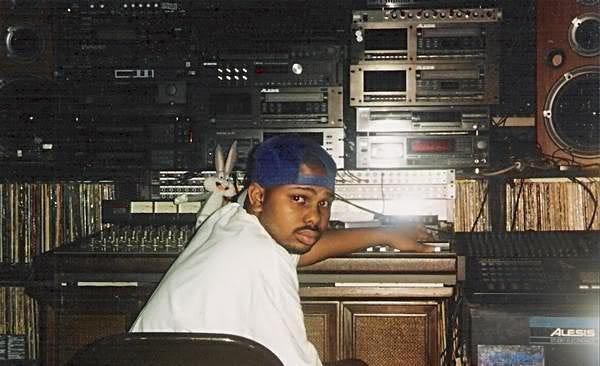

Bay Area native Ant Banks’ discography is massive—the website Discogs currently lists his production credits at a jaw-dropping total of 169 songs. Though his name is likely familiar to die-hard fans of Too Short and his Dangerous Crew affiliates like Spice 1, Banks has been relatively quiet since the early 2000s and isn’t as widely known as some other producers with smaller catalogs. There was a time, however, when he was a dominant force in the music industry.

It all began when Banks learned to play several instruments in his school’s band while simultaneously teaching himself to emulate Funkadelic and The Gap Band on his Casio keyboard during the 1980s. By the time high school rolled around towards the end of the decade, he started making DIY tapes with his friend M.C. Ant.

Before long those Banks’ beats and the late M.C. Ant’s lyrics morphed into a hot commodity and spread far beyond the confines of the classroom. “We made our first little tape and took it to school and started selling it,” Banks recalled in a 2007 DubCNN interview with journalist Chad Kiser. “It became popular all over school, and from the school it went all over the city.”

M.C. Ant’s 1988 full-length effort M.C. Ant The Great ended up being Banks’ first official release, with the west coast vet handling production duties alongside fellow Bay Area producer Terry T. Put out by Raw Dog Records as one of the label’s only releases, M.C. Ant The Great sold 80-90,000 units on CD and cassette in the Bay Area alone.

To a modern artist living in an era of declining album sales those numbers are likely staggering—especially when considering they were achieved in such a limited geographic location.

Banks’ success didn’t stop there—far from it. Projects in subsequent years with Pooh-man, Spice-1, and Dangerous Dame yielded sales of 200,000, almost 300,000, and 100,000 respectively.

It wasn’t long before artists all over the Bay Area took notice of Banks and his remarkable track record. “I was doing independent tape, after independent tape, and they was all selling like 200-300,000 units,” Banks told DubCNN. “Just independently, with no label, no nothing. During that time in the Bay, I was the one that if you wanted a whole CD done, I was the man to come see.”

Banks’ numbers are remarkable, no doubt about it. But as he was dominating his region of California, a largely unknown Orlando DJ and producer named Magic Mike was gearing up to sell 5-6 times as many records with the release of his debut album. No stranger to phenomenal success at a young age, Magic Mike first earned himself a radio gig at age 13 with a pause tape mix. By the time he was 22, his DJ Magic Mike And The Royal Posse debut was slated for release on Cheetah Records.

With no distributor to speak of, Mike’s first official album started to move units at a breakneck speed. By selling records to Florida residents directly out of the back of his van, Mike unloaded so many copies of his debut record that he and his team were unable to to keep track. “We didn’t realize what we were or where we were at,” he told Red Bull Music Academy hosts Torsten Schmidt and Emma Warren in a 2004 interview. “Once we counted how many albums we had sold, we were at 1.3 million copies. “

An overwhelming figure for any industry newcomer, Mike admitted that the tremendous financial results were too much for his team to handle and they had to bring in professionals to help with money management. Despite needing outside help, Mike maintained that selling directly to the listener was a critical step in his story and should be a crucial part of any artist’s business model. “Just the humbleness to always know where you came from and how it got started,” he told Red Bull Music Academy. “No one’s going to sell your project better than you.”

When pressed about how he would approach Steve Jobs regarding iTunes (remember, this interview is from 2004), Mike held fast that building your own entity as an artist is essential—that way the major players come to you. In other words, don’t stress the Steve Jobs of the world and focus on yourself. “You have to be able to maintain it—just in case,” he told Red Bull Music Academy. “If they don’t call, well, as long as you’re doing okay on your own, then you sell your records.”

This concept of building up your own catalog and brand no matter what still holds up in a much different industry 15 years later.

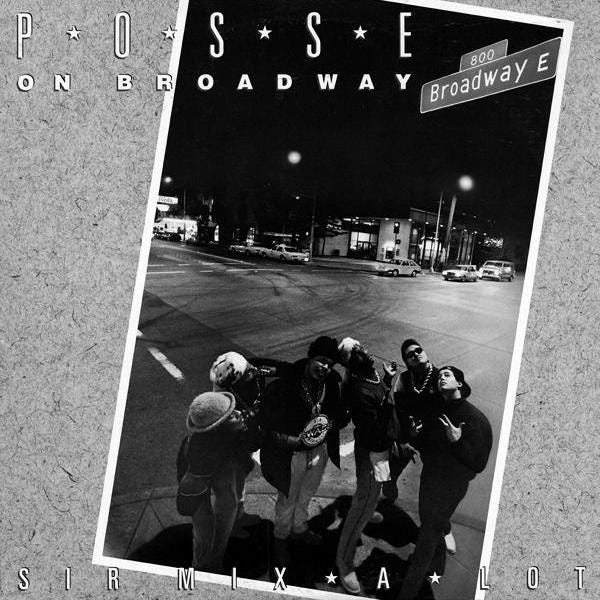

Several years before Ant Banks and Magic Mike moved countless albums in their respective markets, Sir Mix-A-Lot was turning himself into an independent juggernaut in Seattle. After first partnering with local radio DJ Nasty Nes in 1985 to form the NastyMix label, Mix starting making noise with local anthems like “Let’s G” and “The 7 Rainer.”

Even though Mix never bothered putting out “The 7 Rainer” as a proper release on CD, tape, or vinyl, former Seattle radio personality and music journalist Mike Clark thinks it’s one of the most important records from his catalog. The song’s independent success was most definitely an early indicator of things to come. “It was never released, he used to just put them on tape and he would slang his tapes back in the day,” Clark told journalist Andrew Nosnitsky (Noz) in a 2009 Cocaine Blunts interview. “But for a lot of heads here that’s still one of Mix’s biggest songs to never be released on a national basis.”

Mix may have had a loyal following by the mid-80s through his DJ gigs and early NastyMix releases, but it was his 1988 debut album Swass that truly demonstrated how vast his reach was in terms of commercial potential. Dropping the minimalist, 808-laced “Posse on Broadway” as the album’s lead single, Mix somehow made his personal ode to a busy Seattle street a certified hit both in and outside the city.

On the strength of “Posse,” Swass managed to creep onto the Billboard R & B top 20 album chart and eventually went platinum. For a Seattle rapper on an indy label in the 1980s, this was absolutely unheard of.

Further proving his breakthrough success wasn’t a fluke, Mix’s 1989 follow-up effort Seminar moved a very respectable 700,000 units, making him an unparalleled legend in the Seattle rap game. Though financial conflicts with Nes led to a parting of ways with NastyMix 1990, it wasn’t long after that Rick Rubin picked up Mix for his Def American label and put out Mack Daddy and “Baby Got Back” in 1992.

Mix’s massive success an indy artist carried over to his major label endeavors. According to his estimate, “Baby Got Back” has earned a cool $100,000,000 in the 27 years since its release.

Another unforgettable example of independent ingenuity and spirit came out of Houston a few years after the success of Ant Banks, DJ Magic Mike, and Sir Mix-A-Lot in the form of DJ Screw. Known for slowing music down to a glacially slow pace during his DJ sets and mixes while featuring a slew of exclusive freestyles, Screw compiled an almost unfathomable 300+ mixtapes in a seven year span of manic activity from 1993 to 2000.

Now, almost two decades since Screw’s untimely passing, artists continue to marvel at the number of mixtapes he sold to die hard fans in a single day during his prime. “I would watch this man go to car shows and press up literally 10,000 to 15,000 tapes and he would sell out,” Screwed Up Click rapper Lil Flip told DJ Vlad in a 2015 VladTV interview. “He used to have so much money we used to have to count it four and five times.”

Some people have disputed figures like this, but several close friends and collaborators have verified that Screw sold tapes at a level that few DJs have likely ever rivaled. Fellow S.U.C. rapper Z-Ro echoed statistics similar to Flip and further confirmed Screw’s absurd success in a 2015 Noisey interview with Kyle Kramer. “He’d be making like $15,000 a day off his whole catalog,” he said.

Difficult as it may be to believe, Screw never showed an interest in moving on to the majors—even though he was outselling some major label artists with his mixtapes. Strange Music senior executive vice president and general manager David Weiner worked at Priority Records during Screw’s meteoric rise and knew what he was capable, so he offered Screw a deal.

It didn’t take long for the Houston legend to turn it down.

“It wasn’t about the money for him,” Weiner told Soren Baker in a 2001 MTV News interview. “It was about doing what he wanted to do with his homeboys.”

Thanks for reading, see you on Friday!