DJ Premier and the Importance of a DJ Mentality

How a Guru ultimatum, a desire for more creative control, and live scratching loops helped Preemo evolve as a producer.

No matter how much DJ Premier’s massive discography has expanded during his legendary 30-year career, the art of DJing always remains an essential part of his production process. From legendary cut up choruses to live scratched loops, he finds a way to maximize the capabilities of his turntables.

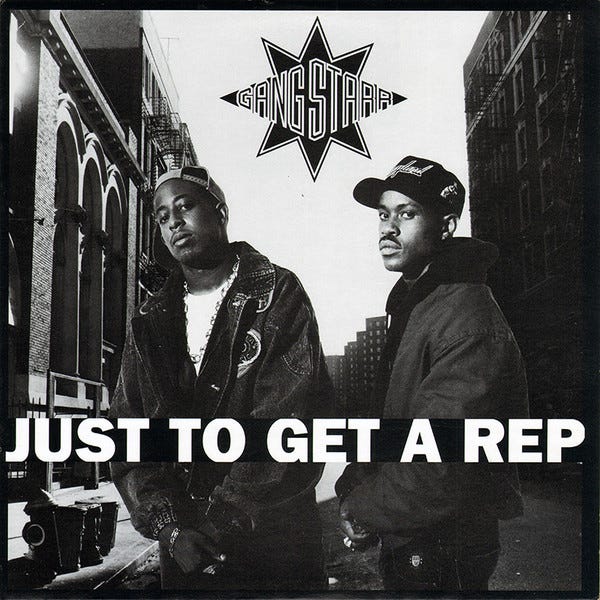

Through many years of providing the beats, cuts, and live DJ duties as one half of Gang Starr, his Live From HeadQCourterz radio show, and countless other DJ gigs, the veteran super producer developed a preternatural gift for picking apart the finite elements of records and rearranging them. “Whenever I produce, I do it with a DJ mentality,” he told Paul Arnold in an outstanding 2011 HipHopDX interview. “When I say a DJ mentality, we pay very close attention to everything that comes out on a record. We dissect it.”

The art of DJing played a particularly critical role during the year-and-a-half span between Gang Starr’s 1989 debut No More Mr. Nice Guy and their seminal 1991 release Step in the Arena, when Preemo’s production abilities transformed from promising newcomer to seasoned sample-chopping vet.

According to Premier, his beatmaking metamorphosis accelerated after late Gang Starr frontman/MC Guru informed him that DJing alone wasn’t enough to earn half of the duo’s revenue. In order to get a fair split, Guru wanted his DJ to craft stronger instrumentals for him to rap over.

But it wasn’t just Guru’s brass tax assessment that made Premier want to step his game up. Relying on others to help shape the group’s sound on No More Mr. Nice Guy made him feel like someone else was in the metaphorical driver’s seat—an experience he wasn’t eager to repeat. “On our first record, I didn’t even program all the beats,” he told Brian Coleman in a unpublished 2001 interview that Ego Trip ran in 2016. “I never wanted to work that way again. I wanted to be in control, I wanted to turn on the machines and do my shit whenever I wanted.”

Living with Guru in a Bronx apartment sublet when the Step in the Arena sessions started, Premier took control of Gang Starr’s sound by honing his DJ skills and scratch looping samples that caught his ear. “I used to just practice everyday—just looping on turntables the parts that I wanted,” he told HipHopDX. “And I’d mark the records and set ‘em aside.”

The first beat to make the cut for Step in the Arena was the title track. Next came “Who’s Gonna Take The Weight?,” a memorable moment of creation that Premier still recalled with vivid detail 20 years later. “I was cuttin’ that little horn whistle [from Maceo & The Macks’ “Parrty”] over and over with two copies,” he told HipHopDX. “And I would just mark all this stuff down on a piece of paper and make it happen.”

Using the horn whistle was partially due to equipment limitations and subsequent innovation, but there was also another driving force behind the somewhat dissonant sample. It was a sound of an era— a moment in time when Bomb Squad-produced Public Enemy cuts were pushing the boundaries of sampling and music in general to fit the tenor of the lyrics. “It was all about noise and screaming and wailing horns and just [trying to] sound like we’re rioting or just fighting for respect and freedom,” Premier told HipHopDX. “I just wanted to do my interpretation of that.”

Premier’s turntable mastery was omnipresent, even on non-album cuts like the “Lovesick” b-side “Credit Is Due.” Give the song a spin and you’ll notice him cutting up a subtle put powerful James Brown vocal sample to give the record some additional punch. “Since I’m a DJ, I got to have DJ elements in there,” he told Jaeki Cho in a 2011 Complex interview. “I would always have turntable elements in my records even if it was just one scratch.”

With a growing skill level and increased access to sophisticated equipment in the years following the release of Step in the Arena, Preemo learned to play keys and started incorporating live playing into his instrumentals. But no matter how much his musical mastery increased or how restrictive sample laws became in the years after Gang Starr’s first two records, using the turntable as an instrument remained a go-to move.

In fact, one of his two contributions to Biggie’s 1997 album Life After Death is mainly made up of Premier cutting up a loop live. “That loop is me sampling my scratching by hand,” he told Gail Mitchell in a 2000 Billboard magazine article on the evolution of sampling. “It was me experimenting, and it sounded dope.”

Whether live scratching a loop or chopping samples up on an MPC, Premier never loses sight of the most important thing—making his audience feel something when they listen to his songs. To him, producing something evocative is always the ultimate goal when rearranging recorded music. “Sampling is all about placement,” he told Billboard. “Where it emotionally grabs you and makes your head nod.”

Give Gang Starr’s surprise seventh and final studio album One of the Best Yet a spin and you’ll hear that Premier is still able to achieve both of these goals with ease.

Thanks for reading, see you on Wednesday!